La Naissance du Jazz

JC Benzekri,

Des Schtetls à Broadway

Comment Juifs et noirs, persécutés, ont lutté pour une universalité de l'Homme ... et comment, ensemble, ils y ont réussi

Ce film-documentaire musical , coproduit par la Chaîne de TV ARTE et Artline Films, retrace l'histoire de la migration des juifs de l’Europe de l’Est vers l'Amérique, du début du XXème siècle jusqu'avant la seconde Guerre mondiale, à travers la musique des Shtetls du Vieux Monde Yiddish, jusqu'aux comédies musicales de Broadway...de l'exode au succès, avec pour héros, Fanny Brice, Sophie Tucker, les Barry Sisters, Al Jolson, George Gershwin, Benny Goodman, Irving Berlin et tant d'autres...

En trois ans la réalisatrice a visionné et assemblé près de 3000 morceaux de films tournés de 1896 à 1945, dont certaines très rares et inédites : des extraits de spectacles et concerts filmés, de courts-métrages musicaux, de comédies musicales américaines et yiddishes, de spectacles comiques américains, de dessins animés...

Les 100 films tournés en yiddish entre 1910 et 1945, surtout en Amérique mais aussi en Russie et en Pologne, sont peu connus du grand public. Comédies musicales pour la plupart, ces films ont pour thèmes principaux l'immigration, le conflit générationnel dû à l'inévitable assimilation exigée par l'intégration.

La réalisatrice

Fabienne Rousso-Lenoir est journaliste, collaboratrice régulière au magazine "Elle" depuis 1983, cinéaste et écrivain, mais aussi juriste en droit international des droits de l'homme, elle travaille sur les rapports entre mémoire et histoire. Ses trois films, dont les deux premiers sont muets, ont en commun de faire une large part à l'élément sonore et musical qui y tient une place aussi importante que le traitement de l'image. "Zakhor", sa très émouvante "cantate en forme de film" a obtenu, entre autre distinctions, le « Gold Hugo Award » au Festival International du Film de Chicago en 1996.

Contexte historique et l’histoire de la naissance du Jazz par Jean-Claude Benzekri :

Déportés d’Afrique de l’Ouest depuis le 17ème siècle, les esclaves noirs ont connu un sort cruel : Familles dispersées, rites ancestraux et musiques interdits, sans identité, ils n’ont plus que le grain de leur voix et la couleur de leur peau pour se réinventer un peuple et retrouver enfin une âme.

Dès le 18ème siècle, les noirs se réunissent par centaine à l’occasion de la Pentecôte, car coupés de leurs racines et privés de leur Dieux, ils trouvent leur place dans les églises et adaptent sous forme de négro-spirituals, la tradition protestante des blancs. Issu de cette

musique, le Gospel-Song marque profondément l’ensemble de la musique populaire des deux derniers siècles.

Chantés par les noirs, les ballades folkloriques des blancs se teintent de « notes bleues », une couleur bleue pour peindre la douleur des noirs.

On fait remonter la terminologie du « Blues » en Angleterre au 16ème siècle où l’état dépressif était alors attribué à l’Empire du « Blue Devil » (Diable Bleu). On disait : a fit blue, un coup de cafard. Au début du 19ème siècle: I have the blues : Je suis déprimé ; en fait, ce que ressentent les populations noires, après la brève lueur d’espoir qui suivit l’abolition de l’esclavage à l’issue de la Guerre de Sécession … et les noirs s’abandonnent au « Blues » pour commenter l’actualité de leur vie.

Au sortir de l’esclavage, les noirs américains s’approprient la lutherie européenne : les instruments à corde des bals de campagne, les pianos des salons bourgeois, les instruments à vent et à percussion des fanfares. Sous l’influence de la tradition, européenne, les noirs inventent une grande école de piano : le « Ragtime ». Dans les rues de la Nouvelle Orléans, une folle musique prend naissance : le « Jazz ».

Entre 1880 et 1924, plus de 2 500 000 Juifs débarquent en Amérique, dont plus 1 600 000 entre 1901 et 1914. A mesure que l'Amérique va donner une nouvelle mutation de l'être juif, la musique et la chanson populaire juive-américaine, à travers les spectacles qu'elles vont engendrer, forgeront à son tour l'identité culturelle de l'Amérique moderne.

L'Amérique que les juifs découvrent en débarquant à Ellis Island n'est pas la Terre Promise, accueillante et égalitaire, dont ils ont tant rêvée. Légalement ouverte aux immigrants, l'Amérique leur reste socialement fermée. Mais pour les Juifs, aucun retour en arrière n'est possible. La seule voix est celle de l'intégration, et la leur passe par celle de tous.

Sur ce continent dont la dynamique va bouleverser leurs traditions et leur culture ancestrale, c'est la musique qui sera leur facteur d'unité ; sur cette planète inconnue dont ils ignorent le langage, elle qui sera leur plus sûr moyen de communication. Portés sur les ailes de leur désir, les enfants du ghetto iront bâtir de toutes pièces leur rêve américain, en façonner les formes d'expression autant que d'illusion.

Ce rêve de la terre promise, d'une communauté où tous existent à chances égales, les artistes juifs le projettent sans relâche sur les pages des partitions, sur les scènes de théâtre, et de Music Halls, sur les écrans de cinéma. A Tin Pan Alley, à Broadway, à Hollywood. Avec deux clefs universelles, l'émotion et l'humour, ils s'imposeront sur une Amérique anglo-saxonne, blanche, puritaine et protestante pour se mêler au grand melting pot.

A Chicago comme dans toute l’Amérique, de jeunes musiciens blancs se prennent de passion pour la musique venue de la Nouvelle Orléans et ce à partir des années 1920 où New York gagne le titre de Capitale du Jazz.

Et pour un musicien noir, jouer du Jazz était pour lui aussi une façon de « s’en sortir ».

Tout au long de l’histoire du Jazz, dans leur aspiration à s’imposer à la majorité anglo-saxonne protestante, les différentes vagues d’immigrations juives d’Europe centrale et italienne avaient pactisé avec la communauté noire contre l’immigration irlandaise, d’où nombre de jazzmen blancs d’origine juive.

Il ne faut pas non plus oublier que la prohibition de l’alcool entre 1919 et 1933 a suscité un gigantesque trafic frauduleux contrôlé par les mafias juives et siciliennes lesquelles ouvrent leurs cabarets aux musiciens noirs ; on y trouvait la un des rares sas de communication entre les deux races, la fréquentation des noirs étant interdite aux blancs.

Le nom de ces compositeurs et de ces musiciens juifs est universellement connu :

Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Larry Hart, Benny Goodman, Al Jolson, les Marx Brothers, Sophie Tucker, Fanny Brice, Molly Picon, Eddie Cantor, Abraham Goldfaden, Abe Ellstein, Sholom Secunda, Betty Boop, Ben Pollack, Gene Krupa, Harold Arlen, Artie Shaw, les Barry Sisters, Glenn Miller, ...

A travers leurs compositions, leurs paroles, leurs rythmes, leurs styles, de la mélodie traditionnelle à la chanson populaire, du théâtre yiddish à la comédie musicale, du Klezmer au Ragtime, du Jazz symphonique au Swing, ce film raconte l'histoire merveilleuse de la métamorphose d'une mélodie.

Noirs et juifs, tous sortis d’un univers de souffrance, de racisme de haine sont unis au début du 20ème siècle afin de vaincre le racisme. Avec l appui au combat de Martin Luther King, qui était leur ami, la victoire de ce combat s’annonce avec l’élection en 2008 du premier Président noir, Barack Obama, démocrate, appuyé par la communauté juive. La politique a enfin rejoint la Musique !

Les Grands du Jazz

George Gershwin, de confession juive est né le 16 Septembre 1898 à Brooklyn ; il meurt le 11 Juillet 1937. Le musicien noir Paul Withman lui commande la « Rhapsodie in Blues », ce concerto de jazz un des plus classiques est créé le 12 février 1922. Puis il y a « Porgy and Bess », interprété par Louis Amstrong et Ella Fitzgerald, « Lady Bee Good » et bien d’autres.

Louis Amstrong, né le 4 Août 1889 et mort le 6 Juillet 1971, est né dans une famille pauvre de la Nouvelle Orléans. Il commence par jouer du cornet à piston, mais son instrument sera la trompette. On le surnomme « Satchmo » à cause de sa bouche en forme de saccoche. Il a acheté son premier instrument avec de l argent prêté par la famille Karnovdky, des juifs originaires de Moscou ; Bing Crosby influencé par Louis Amstrong créé le Jazz chanté.

Irvin Berlin, né le 11 mai 1888 et mort le 22 septembre 1989, se nommait Israël Baline, fils d’un Cantor d’une des très nombreuses synagogues de New York. C’est à Chinatown, au café Pelhmas qu il écrit en une seule portée la musique qu’il jouait avec un seul doigt et certains « spring song » accommodé à la sauce Ragtime la Chanson du Printemps de Mendelsshon. Il fut le plus prolifique auteur américain écrivant plus de 900 chansons et 17 comédies musicales : « Top Hat », « Easter Parage », « Putting in the Ritz », « That Yiddish Jazz », « Yddish Charleston », « Joseph, Joseph »…

Ella Fitzgerald ; née le 25 Mai 1018 à Newport (Virginie) et décédée à Los Angeles le 15 Juin 1986 a été très jeune, chanteuse avec les « Boswell Sisters »Elle fréquente Harlem, les clubs, les dancings. A 17 ans, elle s’inscrit au Harlem Opéra House qui organise un concours qu’elle remporte. Remarquée par la CBS, elle signe son premier contrat. Son chef d’orchestre Chick Webb devient son tuteur légal.

Al Jolson né le 26 Mars 1884 en Russie à Siredzivi est mort le 23 Octobre 1950 à San Francisco. De son vrai nom Asa Yoelson, son père Mosché est Hazan de synagogue. Il lui inculque les règles du chant afin qu’il devienne Rabbin. A Washington, il fuit la maison familiale et chante : « Mammy », « Casino de Paris », et joue dans le premier film parlant « Le Chanteur de Jazz ».

Benny Goodman, né en 1909 à Chicago décède en 1986. Avec sa clarinette magique, il quitte l’école à 14 ans pour devenir musicien. En 1929, il s’installe à New York et est engagé au Music de Billy Rose en 1934. Le 21 Août 1934, à Los Angeles il participe à la création du « Swing ». En introduisant des musiciens noirs dans son orchestre, il brise un tabou. Dans une Amérique ségrégationniste. Benny Goodman a été le premier musicien de Jazz à se produire au Carnegy Hall à New York en 1938, on le nomme : « King of Swing » alors qu’il est le plus grand vendeur de disques. Sans Benny Goodman, le Swing n’aurait probablement jamais vu le jour.

Duke Ellington né le 29 Avril 1899 à Washington DC et mort le 24 Mai 1974 à New York. De par son apparence aristocratique et de son style de vie bourgeois que ses amis l’ont surnommé le « Duke » . A 7 ans il prend des cours de piano, à 16 ans, il compose un ragtime « Soda Fountain Rag ». En 1923, il créé son premier orchestre et fait son premier enregistrement à 24 ans. Il est à la fois Chef d’orchestre et soliste. En 1927, il se produit au « Cotton Club ». Il manie avec génie l’esprit du Blues et il s’avère comme étant un maître du Swing. Son orchestre a été mondialement connu, il semble éternel puisqu’après son fils Mercer, son chef est aujourd’hui Barry Lee Hall Jr. Grâce à sa musique les barrières du racisme ont été repoussées.

On retrouve parmi ses principaux partenaires Sidney Bechet, C Mingus, Al Jolson, Jimmy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Lionel Hampton, Colman Hawkins, Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Mills Davis, Django Reinhart et bien d’autres.

Jean-Claude Benzekri

Rechercher dans ce blog

samedi 23 septembre 2017

Juifs de Suisse

Sources CICAD Suisse

BCH

BCH

Il y a des Juifs Suisses !!

Des artisans et commerçants juifs se sont installés dans les cités romaines de Suisse très tôt, mais on révèle leur présence entre le IIIe et le IVe siècle, mais les premiers documents les mentionnant ne datent que du XIIIe siècle. Pendant les deux siècles suivants, les Juifs ont régulièrement été faussement accusés de tuer des enfants chrétiens ou d’empoisonner des puits. Ils ont souvent subi des discriminations antisémites qui les obligeaient à porter un signe distinctif sur leurs vêtements, à payer des impôts supplémentaires ou à vivre dans des quartiers réservés. Ils ont été expulsés de toutes les villes de Suisse entre 1384 et 1491. Quelques familles ont toutefois bénéficié de la tolérance d’autorités locales, notamment dans les villages argoviens de Lengnau et Endingen, qui ont admis des Juifs en qualité « d’étrangers protégés » dès 1622. A cette époque, les Juifs restent interdits de certaines fonctions (dans la politique et l’agriculture, notamment), raison pour laquelle ils choisissent des professions dans le commerce et les activités bancaires, longtemps interdites aux Chrétiens.

Ce n’est qu’au début du XIXe siècle que des communautés peuvent à nouveau se constituer, à l’initiative de Juifs alsaciens. Des synagogues sont construites à Bâle, Genève, Zurich, St-Gall, Bremgarten, Lucerne et Liestal dès 1852. Une vingtaine de communautés vont s’établir peu à peu.

Pourtant, les Juifs de Suisse ont été parmi les derniers en Europe à obtenir l’égalité politique, en 1866, sous la pression étrangère. Ils ont désormais le droit de s’installer et de travailler où bon leur semble et de jouir des mêmes droits que les citoyens chrétiens. En 1893, un vote populaire interdit l’abattage traditionnel (voir Nourriture cachère*). Cette interdiction est toujours en vigueur aujourd’hui, cas particulier en Europe avec la Suède.

A côté des synagogues, les Juifs ont construit des centres communautaires où sont dispensés des cours d’instruction religieuse pour les enfants, des enseignements de pensée juive pour adultes, où se réunit le Comité directeur de la communauté et où sont organisées des activités d’entraide (prise en charge des pauvres et des orphelins, visite aux malades) et culturelles. Les Juifs acquièrent également des terrains pour leurs cimetières. A cette époque, les Juifs travaillent surtout dans le commerce de chevaux et de bestiaux, dans l’industrie textile et horlogère.

Les Juifs se sont rapidement intégrés à leur environnement. De la même manière que la société s’est ouverte à eux, ils se sont ouverts à la société : habitudes vestimentaires, études et formation professionnelle, service militaire, engagement politique.

Malheureusement, l’antisémitisme n’a pas faibli avec le temps. Il s’est exprimé de manière particulièrement vive dans les années 30 et pendant la guerre : tampon J sur les passeports des Juifs allemands et autrichiens cherchant refuge en Suisse (1938), refoulement de plusieurs milliers de réfugiés juifs, spoliation de comptes en banque, de primes d’assurance, d’œuvres d’art. Si les Juifs de Suisse ont été épargnés par la déportation vers les camps nazis, ils ont néanmoins souffert de discriminations. Ces questions liées à l’attitude de la Suisse pendant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale ont ressurgi dans le débat public en 1995, provoquant également une nouvelle vague d’antisémitisme.

Après la guerre, la population juive de Suisse a poursuivi son intégration, en recevant notamment des charges universitaires, politiques ou culturelles importantes. Ainsi, Ruth Dreyfuss a été Présidente de la Confédération en 1999.

La population juive de Suisse a toujours été plus ou moins stable, aux alentours de 25 000 personnes.

Les communautés juives les plus importantes en Suisse sont celles de Zurich, Genève, Bâle, Lausanne et Berne. Il existe également des communautés plus petites à Fribourg, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Baden, St-Gall, Endingen, Bienne, Vevey-Montreux, Bremgarten, Kreuzlingen, Soleure et Winterthour. Le judaïsme suisse est traditionaliste.

Il existe aussi des communautés libérales à Genève et Zurich et des communautés ultra-orthodoxes à Zurich, Genève, Lugano, Lucerne, Bâle. Les origines géographiques sont très variées : familles alsaciennes au départ, bientôt rejointes par des immigrés d’Europe de l’Est et de l’Empire ottoman au début du XXe siècle. Aux Juifs allemands réfugiés avant la guerre ce sont ensuite ajoutés, dans les années 50 et 60, des Juifs venus des pays arabes.

La majorité des communautés sont ashkénazes, même si la proportion de séfarades et d’orientaux devient majoritaire à Genève et Lausanne. On peut visiter les synagogues et cimetières en prenant rendez-vous avec la communauté locale. Signalons l’existence d’un musée juif à Bâle, dont la collection reflète le patrimoine de la région.

Les Juifs en Normandie

Extraits de la Maison Sublime

BCH

| Le royaume juif |

vendredi 22 septembre 2017

L'Haplotype des Cohanim (Wikipedia)

Wilipédia

L'haplotype modal Cohen ("Y-Aaron gene")

Article détaillé : Gène Y-Aaron.

Récemment, la tradition que les cohanim descendent d'Aaron pourrait avoir reçu un support par l'étude génétique menée à l'université de Haïfa17. Comme tous les lignages patrilinéaires doivent partager un chromosome Y commun, le test a été réalisé parmi les populations juives possédant une telle transmission patrilinéaire (en clair, les cohanim et les Lévites) afin d'établir ou d'infirmer une communauté dans leurs chromosomes Y.

Y-chromosomal Aaron is the name given to the hypothesized most recent common ancestor of the majority of the patrilineal Jewish priestly caste known as Kohanim (singular "Kohen", also spelled "Cohen"). According to the Hebrew Bible, this ancestor was Aaron, the brother of Moses.

The original scientific research was based on the hypothesis that a majority of present-day Jewish Kohanim share a pattern of values for six Y-STR markers, which researchers named the Cohen Modal Haplotype (CMH).[

Subsequent research using twelve Y-STR markers indicated that about half of contemporary Jewish Kohanim shared Y-chromosomal J1 M267, (specifically haplogroup J-P58, also called J1c3), while other Kohanim share a different ancestry, including haplogroup J2a (J-M410).

Molecular phylogenetics research published in 2013 and 2016 for haplogroup J-M267 places the Y-chromosomal Aaron within subhaplogroup Z18271, age estimate 2638-3280 years Before Present (yBP).[

Background

For human beings, the normal number of chromosomes is 46, of which 23 are inherited from each parent. Two chromosomes, the X and Y, determine sex. Women have two X chromosomes, one inherited from each of their parents. Men have an X chromosome inherited from their mother, and a Y chromosome inherited from their father.

Males who share a common patrilineal ancestor also share a common Y chromosome, diverging only with respect to accumulated mutations. Since Y-chromosomes are passed from father to son, all Kohanim men should theoretically have nearly identical Y chromosomes; this can be assessed with a genealogical DNA test. As the rate that mutations accumulate on the Y chromosome is relatively constant,[citation needed] scientists can estimate the elapsed time since two men had a common ancestor. (See molecular clock.)

Although Jewish identity has, since at least the second century CE, been passed by matrilineal descent according to Orthodox tradition (see: Who is a Jew?), membership in the group that comprises the Jewish priesthood (Kehuna), has been determined by patrilineal descent (see Presumption of priestly descent). Modern Kohanim are regarded in Judaism as male descendants of biblical Aaron, a direct patrilineal descendant of Abraham, according to the lineage recorded in the Tanakh (שמות / Sh'mot/Exodus

Initial study

The Kohen hypothesis was first tested through DNA analysis in 1997 by Prof. Karl Skorecki and collaborators from Haifa, Israel. In their study, "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests," published in the journal Nature,[4] they found that the Kohanim appeared to share a different probability distribution compared to the rest of the Jewish population for the two Y-chromosome markers they tested (YAP and DYS19). They also found that the probabilities appeared to be shared by both Sephardic and Ashkenazi Kohens, pointing to a common Kohen population origin before the Jewish diaspora at the Destruction of the Second Temple. However, this study also indicated that only 48% of Ashkenazi Kohens and 58% of Sephardic Kohens have the J1 Cohen Modal Haplotype.

In a subsequent study the next year (Thomas MG et al., 1998),[1] the team increased the number of Y-STR markers tested to six, as well as testing more SNP markers. Again, they found that a clear difference was observable between the Kohanim population and the general Jewish population, with many of the Kohen STR results clustered around a single pattern they named the Kohen Modal Haplotype:

xDE[4] xDE,PR[1] Hg J[5] CMH.1[1] CMH[1] CMH.1/HgJ CMH/HgJ Ashkenazi Cohanim (AC): 98.5% 96% 87% 69% 45% 79% 52% Sephardic Cohanim (SC): 100% 88% 75% 61% 56% 81% 75% Ashkenazi Jews (AI): 82% 62% 37% 15% 13% 40% 35% Sephardic Jews (SI): 85% 63% 37% 14% 10% 38% 27%

Here, becoming increasingly specific, xDE is the proportion who were not in Haplogroups D or E (from the original paper); xDE,PR is the proportion who were not in haplogroups D, E, P, Q or R; Hg J is the proportion who were in Haplogroup J (from the slightly larger panel studied by Behar et al. (2003)[5]); CMH.1 means "within one marker of the CMH-6"; and CMH is the proportion with a 6/6 match. The final two columns show the conditional proportions for CMH.1 and CMH, given membership of Haplogroup J.

The data show that the Kohanim were more than twice as likely to belong to Haplogroup J than the average non-Cohen Jew. Of those who did belong to Haplogroup J, the Kohanim were more than twice as likely to have an STR pattern close to the CMH-6, suggesting a much more recent common ancestry for most of them compared to an average non-Kohen Jew of Haplogroup J.

| xDE[4] | xDE,PR[1] | Hg J[5] | CMH.1[1] | CMH[1] | CMH.1/HgJ | CMH/HgJ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashkenazi Cohanim (AC): | 98.5% | 96% | 87% | 69% | 45% | 79% | 52% | |

| Sephardic Cohanim (SC): | 100% | 88% | 75% | 61% | 56% | 81% | 75% | |

| Ashkenazi Jews (AI): | 82% | 62% | 37% | 15% | 13% | 40% | 35% | |

| Sephardic Jews (SI): | 85% | 63% | 37% | 14% | 10% | 38% | 27% |

Dating

Thomas, et al. dated the origin of the shared DNA to approximately 3,000 years ago (with variance arising from different generation lengths). The techniques used to find Y-chromosomal Aaron were first popularized in relation to the search for the patrilineal ancestor of all contemporary living humans, Y-chromosomal Adam.

Molecular phylogenetic research published in 2013 and 2016 for haplogroup J-M267 places the Y-chromosomal Aaron within subhaplogroup Z18271, age estimate 2638-3280 years Before Present (yBP).

Responses

The finding led to excitement in religious circles, with some seeing it as providing some proof of the historical veracity of the Priestly covenant[6] or other religious convictions.

Following the discovery of the very high prevalence of 6/6 CMH matches amongst Kohanim, other researchers and analysts were quick to look for it. Some groups have taken the presence of this haplotype as indicating possible Jewish ancestry, although the chromosome is not exclusive to Jews. It is widely found among other Semitic peoples of the Mideast.

Some persons said that the 6/6 matches found among male Lemba of Southern Africa confirmed their oral history of descent from Jews and connection to Jewish culture.(Thomas MG et al. 2000); Dissenting interpretations however have been advanced in some recent research.[

Some researchers suggested that 4/4 matches found in non-Jewish Italians might be a genetic inheritance from Jewish slaves. They were deported from Judea by Emperor Titus in large numbers after the fall of the Temple in AD 70. Some men were put to work building the Colosseum in Rome. They were the start of a substantial Jewish community in Rome that developed in the early centuries of the Common Era.

Critics such as Avshalom Zoosmann-Diskin suggested that the paper's evidence was being overstated in terms of showing Jewish descent among these distant populations.[

Limitations

Principal components analysisscatterplot of Y-STR haplotypes from Haplogroup J, calculated using 6 STRs. With only six Y-STRs, it is not possible to resolve the different subgroups of Hg J.

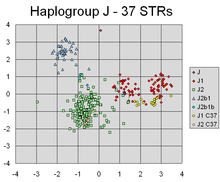

Principal components analysisscatterplot of Y-STR haplotypes from Haplogroup J, calculated using 37 STRs. With 37 Y-STR markers, clearly distinct STR clusters can be resolved, matching the distinct J1, J2 and J2b subgroups. The haplotypes often associated with Cohen lineages in each group are highlighted as J1 C37 and J2 C37, respectively.

One source of early confusion was the low resolution and general coverage of the Cohen Modal Haplotype. The Cohen Modal Haplotype (CMH), while frequent amongst Kohanim, also appeared in the general populations of haplogroups J1 and J2 with no particular link to the Kohen ancestry. These haplogroups occur widely throughout the Middle East and beyond.[ Thus, while many Kohanim have haplotypes close to the CMH, a greater number of such haplotypes worldwide belong to people with no apparent connection to the Jewish priesthood.

Individuals with at least 5/6 matches for the original 6-marker Cohen Modal Haplotype are found across the Middle East, with significant frequencies among various Arab populations, mainly those with the J1 Haplogroup. These have not been "traditionally considered admixed with mainstream Jewish populations" – the frequency of the J1 Haplogroup is the following: Yemen (34.2%), Oman (22.8%), Negev (21.9%), and Iraq (19.2%); and amongst Muslim Kurds (22.1%), Bedouins (21.9%), and Armenians (12.7%).[

On the other hand, Jewish populations were found to have a "markedly higher" proportion of full 6/6 matches, according to the same (2005) meta-analysis.[15] This was compared to these non-Jewish populations, where "individuals matching at only 5/6 markers are most commonly observed.

The authors Elkins, et al. warned in their report that "using the current CMH definition to a infer relation of individuals or groups to the Kohen or ancient Hebrew populations would produce many false-positive results," and note that "it is possible that the originally defined CMH represents a slight permutation of a more general Middle Eastern type that was established early on in the population prior to the divergence of haplogroup J. Under such conditions, parallel convergence in divergent clades to the same STR haplotype would be possible.

Cadenas et al. analysed Y-DNA patterns from around the Gulf of Oman in more detail in 2007.[16] The detailed data confirm that the main cluster of haplogroup J1 haplotypes from the Yemeni appears to be some genetic distance from the CMH-12 pattern typical of eastern European Ashkenazi Kohanim, but not of Sephardic Kohanim.

Principal components analysisscatterplot of Y-STR haplotypes from Haplogroup J, calculated using 6 STRs. With only six Y-STRs, it is not possible to resolve the different subgroups of Hg J.

Principal components analysisscatterplot of Y-STR haplotypes from Haplogroup J, calculated using 37 STRs. With 37 Y-STR markers, clearly distinct STR clusters can be resolved, matching the distinct J1, J2 and J2b subgroups. The haplotypes often associated with Cohen lineages in each group are highlighted as J1 C37 and J2 C37, respectively.

Multiple ancestries

Even within the Jewish Kohen population, it became clear that there were multiple Kohen lineages, including distinctive lineages both in Haplogroup J1 and in haplogroup J2.[17] Other groups of Jewish lineages (i.e. Jews who are non-kohanim) were found in Haplogroup J2 that matched the original 6-marker CMH, but which were unrelated and not associated with Kohanim. Current estimates, based on the accumulation of SNP mutations, place the defining mutations that distinguish haplogroups J1 and J2 as having occurred about 20 to 30,000 years ago.

Subsequent studies

In response to the low resolution of the original 6-marker CMH, the testing company FTDNA released a 12-marker CMH signature that was more specific to the large, closely related group of Kohanim in Haplogroup J1.

A 2009 academic study by Michael F. Hammer, Doron M. Behar, et al. examined more STR markers in order to sharpen the "resolution" of these Kohanim genetic markers, thus separating both Ashkenazi and other Jewish Kohanim from other populations, and identifying a more sharply defined SNP haplogroup, J1e* (now J1c3, also called J-P58*) for the J1 lineage. The research found "that 46.1% of Kohanim carry Y chromosomes belonging to a single paternal lineage (J-P58*) that likely originated in the Near East well before the dispersal of Jewish groups in the Diaspora. Support for a Near Eastern origin of this lineage comes from its high frequency in our sample of Bedouins, Yemenis (67%), and Jordanians (55%) and its precipitous drop in frequency as one moves away from Saudi Arabia and the Near East (Fig. 4). Moreover, there is a striking contrast between the relatively high frequency of J-58* in Jewish populations (»20%) and Kohanim (»46%) and its vanishingly low frequency in our sample of non-Jewish populations that hosted Jewish diaspora communities outside of the Near East."[18] The authors state, in their "Abstract" to the article:

- "These results support the hypothesis of a common origin of the CMH in the Near East well before the dispersion of the Jewish people into separate communities, and indicate that the majority of contemporary Jewish priests descend from a limited number of paternal lineages

Recent phylogenetic research for haplogroup J-M267 placed the "Extended Cohen Modal Haplotype" in a subhaplogroup of J-L862,L147.1 (age estimate 5631-6778yBP yBP): YSC235>PF4847/CTS11741>YSC234>ZS241>ZS227>Z18271 (age estimate 2731yBP).

A 2014 article analysing earlier research attempting to trace Jewish ancestry (not just of the Lemba) states:

In conclusion, while the observed distribution of sub-clades of haplotypes at mitochondrial and Y chromosome non-recombinant genomes might be compatible with founder events in recent times at the origin of Jewish groups as Cohenite, Levite, Ashkenazite, the overall substantial polyphyletism as well as their systematic occurrence in non-Jewish groups highlights the lack of support for using them either as markers of Jewish ancestry or Biblical tales.

In conclusion, while the observed distribution of sub-clades of haplotypes at mitochondrial and Y chromosome non-recombinant genomes might be compatible with founder events in recent times at the origin of Jewish groups as Cohenite, Levite, Ashkenazite, the overall substantial polyphyletism as well as their systematic occurrence in non-Jewish groups highlights the lack of support for using them either as markers of Jewish ancestry or Biblical tales.

Kohanim in other haplogroups

Behar's 2003 data[ point to the following Haplogroup distribution for Ashkenazi Kohanim (AC) and Sephardic Kohanim (SC) as a whole:

Hg: E3b G2c H I1b J K2 Q R1a1 R1b Total AC 3 0 1 0 67 2 0 1 2 76 4% 1½% 88% 2½% 1½% 2½% 100% SC 3 1 0 1 52 2 2 3 4 68 4½% 1½% 1½% 76% 3% 3% 4½% 6% 100%

The detailed breakdown by 6-marker haplotype (the paper's Table B, available only online) suggests that at least some of these groups (e.g. E3b, R1b) contain more than one distinct Kohen lineage. It is possible that other lineages may also exist, but were not captured in the sample.

Hammer et al. (2009) identified Cohanim from diverse backgrounds, having in all 21 differing Y-chromosome haplogroups: E-M78, E-M123, G-M285, G-P15, G-M377, H-M69, I-M253, J-P58, J-M172*, J-M410*, J-M67, J-M68, J-M318, J-M12, L-M20, Q-M378, R-M17, R-P25*, R-M269, R-M124 AND T-M70.[18]

| Hg: | E3b | G2c | H | I1b | J | K2 | Q | R1a1 | R1b | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 67 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 76 | |

| 4% | 1½% | 88% | 2½% | 1½% | 2½% | 100% | |||||

| SC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 52 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 68 | |

| 4½% | 1½% | 1½% | 76% | 3% | 3% | 4½% | 6% | 100% |

Y-chromosomal Levi

Similar investigation was made of men who identify as Levites. The priestly Kohanim are believed to have descended from Aaron (among those who believe he was an historic figure). He was a descendant of Levi, son of Jacob. The Levites comprised a lower rank of the Temple than the priests. They are considered descendants of Levi through other lineages. Levites should also therefore share common Y-chromosomal DNA.

The investigation of Levites found high frequencies of multiple distinct markers, suggestive of multiple origins for the majority of non-Aaronid Levite families. One marker, however, present in more than 50% of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish Levites, points to a common male ancestor or very few male ancestors within the last 2000 years for many Levites of the Ashkenazi community.

This common ancestor belonged to the haplogroup R1a1, which is typical of Eastern Europeans or West Asians, rather than the haplogroup J of the Cohen modal haplotype. The ancestor(s) most likely lived at the time of the Ashkenazi settlement in Eastern Europe, and would thus be considered founders of this line. He or they were unlikely to have descended from Levites.

But, a study published online in Nature Communications in December 2013 disputes this conclusion. Based on its research into 16 whole R1 sequences, the team determined that a set of 19 unique nucleotide substitutions defines the Ashkenazi R1a lineage. One of these, the M582 mutation, is not widely found among Eastern Europeans, but this marker was present "in all sampled R1a Ashkenazi Levites, as well as in 33.8% of other R1a Ashkenazi Jewish males, and 5.9% of 303 R1a Near Eastern males, where it shows considerably higher diversity." Rootsi, Behar, et al., concluded that this marker most likely originates in the pre-Diasporic Hebrews in the Near East.

The E1b1b1 haplogroup (formerly known as E3b1) has been observed in all Jewish groups worldwide. After the J halogroups, it is considered to be the second-most prevalent haplogroup among the Jewish populations.

Samaritan Kohanim

The Samaritan community in the Middle East survives as a distinct religious and cultural sect. It constitutes one of the oldest and smallest ethnic minorities in the world, numbering sightly less than 800 members. According to Jewish accounts, the Samaritans broke away from the mainstream Israelites as a religious sect around the eighth century B.C. According to Samaritan accounts, it was the southern tribes of the House of Judah who left the original worship as set forth by Joshua, and the schism took place in the twelfth century B.C. at the time of Eli.

The Samaritans have maintained their religion and history to this day, and claim to be the remnant of the House of Israel, specifically of the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh with priests of the line of Aaron/Levi.

Since the Samaritans have maintained extensive and detailed genealogical records for the past 13–15 generations (approximately 400 years) and further back, researchers have constructed accurate pedigrees and specific maternal and paternal lineages. A 2004 Y-Chromosome study concluded that the majority of Samaritans belong to haplogroups J1 and J2, while the Samaritan Kohanim belong to haplogroup E1b1b1a (formerly known as E3b1a).

Inscription à :

Commentaires (Atom)